Get started at http://www.coderdojokc.com/today

Welcome to CoderDojoKC! Let’s get you started!

Looking for something to do? Practice your typing skills! Typing.io is a great way to keep your fingers nimble and learn where some of those tricky keys are located.

Are you working on the debugging challenge? Remix it here!

Step One: Wifi

1. Open up your internet connection and connect to “Fiber Public WiFi“

2. Can’t connect? See if you can get to the wifi sign-in at http://google.com/fiber

3. Still can’t connect? Raise your hand and a mentor will get you a hotspot to connect to.

4. We recommend using the Google Chrome browser.

Step Two: Start Learning!

If you don’t know which programming language to start learning, we recommend Scratch (if Scratch is not to your speed, check out the typing.io link in the sidebar on the right).

You will need a parent or guardian’s help to create a Scratch login:

- Click “Join Scratch” in the upper right-hand corner of the Scratch site.

- Create a username that does not include your real name.

- Think of a password that you can remember easily. You should have your parent or guardian write this down and save it.

- Click “Next” and continue following the directions. You will need a valid email address (yours or your guardian’s) to continue.

Once you have a Scratch login, use the links below to build something awesome.

Step Three: Learn to Code

1. Are you brand new to coding? Start with Codecademy (recommended for 13 years & up) or Scratch (recommended for 12 years & under). Want to try building your own phone application? Check out App Inventor! Be sure to create an account and write down your username and password so you won’t forget!

2. Do you have a little coding under your belt? Are you ready to learn more? Check out these fun games:

- CodeAvengers – learn to build JavaScript apps

- CodeCombat -Learn how to code by playing a game

- CSS Diner -A game for learning CSS selectors

- Flexbox Froggy – A game for learning CSS flexbox

- Flexbox Defense – Another game for learning CSS flexbox

- Super Markup Man – learn html

- Untrusted – a user JavaScript adventure game

3. Were you working on a project from our last session? Feel free to continue on that, and ask mentors if you need any help!

4. Get started on the new project. We can’t wait to see what you create!

Step Four: Check Out the Projects

Mastery – Feeling masterful? Check out the requirements for our mastery badges. You can earn cool pins!

Today’s concept: A Year in Review

This past year, we have done quite a few cool projects and concepts. Today’s project is to learn from the past year of projects and concepts and use at least one of those concepts to build anything that you choose.

Winning Projects:

- February Scratch:

- 1: Elivia F. “Make a Kitty“

- 2: Khaliana G. “Soccer Goals“

- February Website: Alexander V. “Coderdojo Project”

- February Surprise: Hudson H. “ESPN Scraper”

- March Scratch:

- 1. Ethan G. “Cup Game“

- 2. Liliana W. “Liliana’s Piano Guessing Game“

- March Website: Rhys W. “The Quiz”

- March Surprise: Jack S. “Skylands”

- April Scratch:

- 1. Molly M. “My Virtual Garden“

- 2. Olivia N. “Grow an Apple Tree!“

- May Scratch:

- 1. Noema W. “Happy Mother’s Day“

- 2. Danielle H. “Happy Mother’s Day“

- June Scratch:

- 1. Unknown “Unknown”

- 2. Noah B. “Fathers Day Gift“

- June Website: Hayes M. “Happy Father’s Day!”

- July Scratch:

- 1. Yusuf S. “AMERICA“

- 2. Noah B. “Teleport Orb“

- August Scratch:

- 1. Gram Z. “True or False!“

- 1. Hannah P. “Save the Black Rhino: The Cutest Animal Ever!“

- September Scratch:

- 1. Zander C. “A Day at Kauffman Stadium“

- 2. Gabriel B. “Hot Dogs for Kansas City“

- October Scratch:

- 1. Ava M. “Apple Catch Speed Up“

- 2. Hayes M. “The Dab Competition“

Mastery Projects:

- Scratch

- Molly M. “Journal PRO“

- Jack M. “Depend”

- Carlos S. “Quiz”

- JavaScript

- Riley M. “Simple but legit calculator”

- Website

- Sam G. “The Official Tubbs Website”

- Henry M. “HTML Mastery”

January: Snowed out!

February’s Concept: Variables

In mathematics, we learn that a variable is something unknown that can take a value. In early math, you might see: 2 + □ = 5; we know that □ is 3. Later on, that becomes 2 + X = 5; we know that X = 3 in order for that math sentence to make sense.

In programming, variables can be something unknown that takes a value, as in the case of a variable that takes the value of something that the user inputs. A variable can also take on the value of something more complicated to make referencing that complicated thing more easy. This can be like setting a variable pi to “3.141592653589” instead of having to type out all of those numbers each time you want to use them.

Perhaps variables can be illustrated with a joke:

A man is sent to prison for the first time. At night, the lights in the cell block are turned off, and his cellmate goes over to the bars and yells, “Number twelve!” The whole cell block breaks out laughing. A few minutes later, somebody else in the cell block yells, “Number four!” Again, the whole cell block breaks out laughing.

The new guy asks his cellmate what’s going on. “Well,” says the older prisoner, “we’ve all been in this here prison for so long, we all know the same jokes. So we just yell out the number instead of saying the whole joke.”

So the new guy walks up to the bars and yells, “Number six!” There was dead silence in the cell block. He asks the older prisoner, “What’s wrong? Why didn’t I get any laughs?”

“Well,” said the older man, “sometimes it’s not the joke, but how you tell it.”

A variable can also be changed; think about having a variable called “high score.”

In Scratch, you can create a data variable and give it a value. The variable can be used by either the sprite or all sprites. You can show your variable and its value on the stage if you want to; this would be useful for a game score.

Additional information about Scratch variables

In JavaScript, you can create a variable and give it a value.

var myCity = "Kansas City";

Additional information about JS variables

February’s Winning Project:

- Scratch:

- 1: Elivia F. “Make a Kitty“

- 2: Khaliana G. “Soccer Goals“

- Website: Alexander V. “CoderDojo Project”

- Surprise: Hudson H. “ESPN Scraper”

March’s Concept: Code Reuse with Functions

Have you ever found yourself repeating your code over and over in Scratch or in JavaScript? If you find yourself doing this, you can take advantage of “functions” to reuse the same code over and over again. In Scratch, functions are called “custom blocks,” but everywhere else, they’re called “functions” and sometimes “methods.”

All functions do something within your code.

Functions can take input and return output. This is like a popcorn popper at the movie theater: you add popcorn kernels and oil, and you get hot popcorn in return.

Other functions are like commands. They don’t take any input, but they do something anyway. It’s like telling your dog to sit. You don’t tell your dog where to sit, how to sit, how long to sit, or when to sit; you just tell your dog to sit. And guess what? Your dog sits. Good dog!

One way to think about functions is that they let you take a bunch of steps and give them a simple name. This is like teaching a robot to speak. You could tell the robot how to speak each time you want the robot to speak, or you can just create a speak function and tell the robot to do it instead.

voiceBox.turnOn();

voiceBox.setVolume(30);

voiceBox.say("Hello");

voiceBox.turnOff();

voiceBox.turnOn();

voiceBox.setVolume(30);

voiceBox.say("I like to play games");

voiceBox.turnOff();

The same, but with functions!

function speak(phrase) {

voiceBox.turnOn();

voiceBox.setVolume(30);

voiceBox.say(phrase); // <-- Here's the part that relies on the input!

voiceBox.turnOff();

}

speak("Hello");

speak("I like to play games");

As you can see, you can create the function once and call it multiple times.

Additional information about Scratch custom blocks

Additional information about JS functions

March’s Winning Project:

- Scratch:

- 1. Ethan G. “Cup Game“

- 2. Liliana W. “Liliana’s Piano Guessing Game“

- Website: Rhys W. “The Quiz”

- Surprise: Jack S. “Skylands”

April’s Concept: Events, Broadcast/Receive, Publish/Subscribe

Today we are going to flex our code-magic muscles and look at events, broadcast/receive (aka publish/subscribe). On a web page or in a game, clicking on a button requires an action or an event (let’s call it “on-click”); that action will broadcast a message (ex. “HEY! The red button was clicked!”) that another part of the program is listening for. Once that message is received, an action will take place (ex. “OK, I now know that the red button was clicked, so I will ignite the rocket”). In Scratch, you would use the “Events” blocks for “broadcast” and “receive.” In JavaScript, you might use the event for “onclick” and run a function.

In a way, this is like casting a spell. You say the words or make the right motion and the appropriate action takes place. I could say “Accio taco!” and wave my arms just so and a taco from my favorite taco stand would fly into my hands. “Accio taco” is the Scratch Broadcast or the JavaScript event, and the taco flying to me would be the Scratch “when I receive” or the JavaScript function.

April’s Winning Project:

- Scratch:

- 1. Molly M. “My Virtual Garden“

- 2. Olivia N. “Grow an Apple Tree!“

May’s Concept: Random

Let’s take a look at a concept that helps make many games interesting, the concept of “random.” If something is random, one has a difficult time predicting its behavior. Many games rely, in a huge part, upon randomness. For instance, in a card game, the dealer will randomize the deck of cards by shuffling the cards; which cards you get are selected from a randomly ordered deck. We roll dice to come up with a random number between 1 & 6. In American Football, a coin is tossed to determine which team starts the game by kicking or by receiving.

Randomness in Nature can be truly random. Computers, on the other hand, thrive on predictability and, therefore, making something truly random on a computer is very difficult. Here at the CoderDojo, we can attempt to use the computer’s definition of random to our advantage to help make certain games more fun to play.

In Scratch, we have two ways of doing something randomly. We can pick a random number between a starting number and an end number.

We can also select a random item from a list.

In JavaScript, we generate a random number and use that to access an item in an array or to show a random number. Because JavaScript random numbers are a decimal between 0 and 1, we have to multiply that random number by however many numbers we want to select from and then round that number down to the nearest whole number. For example:

var randomize = function(things) {

var randomNumber = Math.random() * things.length;

var arrayItem = Math.floor(randomNumber);

return things[arrayItem];

};

This function will take in an array and return a random item from that array.

May’s Winning Project:

- Scratch:

- 1. Noema W. “Happy Mother’s Day“

- 2. Danielle H. “Happy Mother’s Day“

June’s Concept: Proximity

Let’s take a look at a concept that helps make many games interesting: proximity. Proximity tells us how far apart two things are from each other. Many games rely, in a huge part, upon proximity. For instance, in Tic Tac Toe, you must form a line of Xes or Os; we say the shapes that make up the line are in close proximity to one another.

In Scratch, we have two ways of finding proximity. We can automatically get the distance between two sprites with the distance operator:

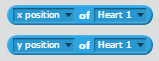

Or we can manually calculate the distance using the X/Y position operator.

June’s Winning Project:

- 1. Unknown “Unknown”

- 2. Noah B. “Fathers Day Gift“

July’s Concept: Text & User Input

If you ask almost any developer-mentor in this room who they write programs for, they will all tell you that they write them for clients, other people. All of these programs rely upon input from those other people in order to be useful. If you think about the games that you love to play, those games are fun to play because they rely upon some kind of input from you — it could be the press of a button, wiggling a joystick, or typing an answer. Today, we’ll look at the a user typing in text in order to provide input for your program.

In Scratch, we have one way of getting user input as text: ![]() . This will ask for input and store that input as an answer variable that you can use later:

. This will ask for input and store that input as an answer variable that you can use later: ![]() .

.

If you ask several questions, you will want to store each of those answers in a different variable before asking another question. ![]()

In JavaScript, you can get user input by using a form. A form can take in text, ask questions where the user has to select either “yes” or “no,” offer a dropdown list for users to select one or more options, and others. Each form part should have a unique ID since that the answer to that part of the form will be tied to the ID.

<input type="text" id="place"> <button type="submit" id="submit">Submit</button>

In JavaScript, you would then pull information out of that form to be used in your code. You can do that by assigning the data tied to those form part IDs to variables.

var place = document.querySelector("#place");

You can then show that answer in a string by using string concatenation.

"I love " + place.value + ", it is such a cool place to visit!"

The Mozilla Developer Network has a great introduction to forms if you’d like to learn more about creating forms in HTML.

July’s Winning Project:

- Scratch:

- 1. Yusuf S. “AMERICA“

- 2. Noah B. “Teleport Orb“

August’s Concept: Multiple Choice & User Input

If you ask almost any developer-mentor in this room who they write programs for, they will all tell you that they write them for clients, other people. All of these programs rely upon input from those other people in order to be useful. If you think about the games that you love to play, those games are fun to play because they rely upon some kind of input from you — it could be the press of a button, wiggling a joystick, or typing an answer. Today, we’ll look at the a user selecting an option in order to provide input for your program.

In Scratch, we have one way of getting user input as a selection, in the form of a button:  . This will fire an event that you can act upon.

. This will fire an event that you can act upon.

In JavaScript, you can get user input by using a form. A form can take in text, ask questions where the user has to select either “yes” or “no,” offer a dropdown list for users to select one or more options, and others. Each form part should have a unique ID since that the answer to that part of the form will be tied to the ID.

<input type="radio" id="firstGroup" value="2013"> October 5, 2013 </input> <button type="submit" id="submit">Submit</button>

In JavaScript, you would then pull information out of that form to be used in your code. You can do that by assigning the data tied to those form group IDs to variables.

var answer = document.querySelector("#firstGroup");

You can then check the answer by using an if-statement.

if (answer == "2013") {

doSomething();

}

The Mozilla Developer Network has a great introduction to forms if you’d like to learn more about creating forms in HTML.

August’s Winning Projects:

- Scratch:

- 1. Gram Z. “True or False!“

- 1. Hannah P. “Save the Black Rhino: The Cutest Animal Ever!“

September’s Concept: None – Free Day to Brag About Kansas City

September is a great month in Kansas City. The weather is usually great, which means it’s a great time to go to festivals, sporting events, outdoor competitions, museums, and more! This week, we have the Old Settlers festival in Olathe, The Youth & Open Horse Show at the American Royal, the annual Art Westport show, Halloween Haunt starts at Worlds of Fun, the Chiefs home opener at Arrowhead, and more!

September’s Winning Project:

- Scratch:

- 1. Zander C. “A Day at Kauffman Stadium“

- 2. Gabriel B. “Hot Dogs for Kansas City“

October’s Concept: Timers — Countdown & Stopwatch

Timing in games can be important. Often, when watching a sporting event, like a Olympic Track, the runners can cross the finish line seemingly at the same time, so who won? Too often, this kind win comes down to determining which athlete ran across the finish line first to the 100th of a second! In 1987, Ed Moses beat two other athletes across the finish line 2 one-hundredths of a second. What determined the win? Timing.

Bonus: See KCWiT’s own, Ann Gaffigan, come across the finish line in the 2004 Olympic Trials.

In software games and other applications, we use timing quite often. Maybe we assign the owner of something to the person who submits it first. Maybe we want to show how long until a planned even occurs. Maybe we want to see how long it took for something to happen.

We can check the time that something occurred, see how long it took for something to happen, or count down until something ends or begins.

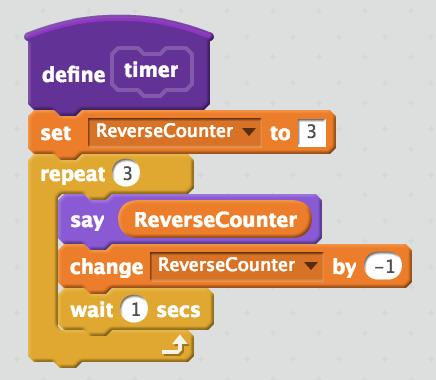

In Scratch, we can count down by putting a for-loop into our code and starting with a large number and decreasing that number until we get to our target number.

If we want to see how long it takes for something to happen, we need to determine the smallest unit of time measurement that makes sense for that thing, and count up by it.

If we want to see how long it takes for something to happen, we need to determine the smallest unit of time measurement that makes sense for that thing, and count up by it.

These two methods are very similar. Can you see it?

October’s Winning Project:

- Scratch:

- 1. Ava M. “Apple Catch Speed Up“

- 2. Hayes M. “The Dab Competition“

**Presentations may not contain any politics, violence, gore, or bad words. (And we’re counting “sucks” as a bad word!)